MEDICAL

CONFLICTS

Diagnose in Decade

It's been more than a year since his nose was broken, but young doctor Wang Ziliang, still doesn’t dare go on night shift at his the hospital. "I don't want to talk about it," he responds when asked about the matter, waving his hand in a gesture of refusal.

The incident in question was not overly complicated. A patient had wanted to skip the necessary formalities and receive his medications directly from Wang, who refused, citing hospital regulations barring doctors from prescribing privately.

What ensued was a violent attack with fists and feet, sending him to the hospital’s ears, nose and throat department for treatment.

Compared with Wang's dread, Liu Linfeng, who has been working in the same hospital’s emergency department for 16 years, is far more circumspect. "It's often the case that I get kicked or slapped," Liu says with a wry smile that seems to denote a resignation to inevitability of occasional violence from patients and their families.

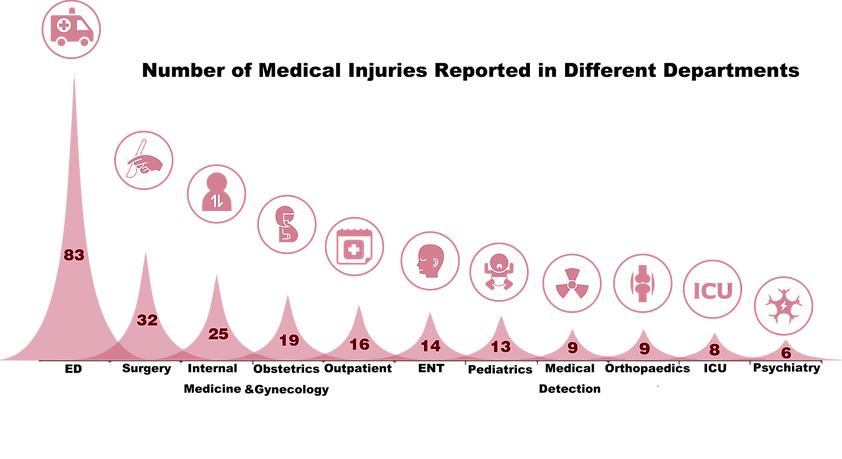

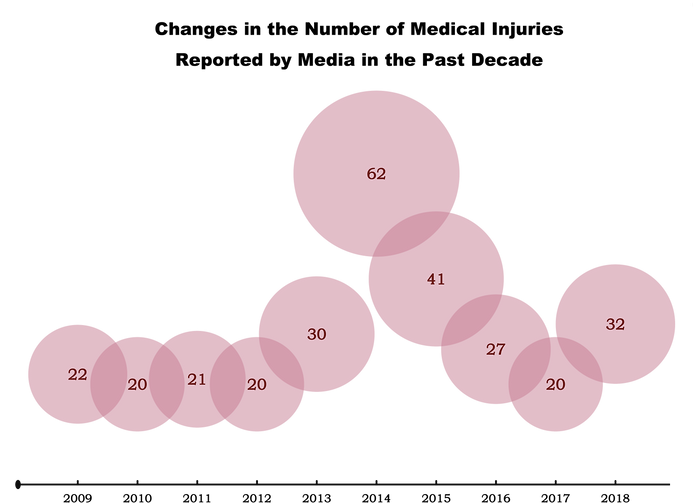

Among all doctors in China, 66% have personally experienced medical conflicts, while over 30% have been subject to violence, according to the White Paper on the Practice of Chinese Physicians released by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association in 2018. In the 295 medical injuries incidents in mainland China reported by official media over the past ten years, 362 medical staff suffered injuries, 99 medical staff were attacked by knives and 24 doctors lost their lives.

Data source: medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

Guangdong province reported the highest number of violent incidents, with a total of 38 cases. Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui and other heavily populated eastern provinces also reported a high number of incidents, while lightly populated western regions such as Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang reported fewer.

Data Source: China Sanitation and Family Planning Statistical Yearbook, 2017;

Medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

The higher the level of hospital, the higher the frequency of reported injuries. Among all reported violent incidents, 70% occurred the largest and best quipped tertiary class hospitals, with the even more elite tertiary-A hospitals accounting for fully half of all incidents

Tertiary-As attract large numbers of patients drawn by their advanced medical equipment, personnel and technical resources. That seems to explain in part why they account for such a large percentage of violent cases, as illustrated by the saying, "big hospital with smashing head, small hospitals with empty bed".

"Many patients with the means are more likely to go to the metropolises such as Beijing or Shanghai to seek medical services. (But) some minor surgeries like appendix operations are so simple that our smaller hospitals can deal with them as well, complained Cui Shumin, an orthopedics nurse at a secondary-tier hospital in Shandong province where half of the beds in her department lie empty. "However, some patients are eager to crowd into tertiary-As even if they have to wait half a year for a spot, while few of them are willing to come to our hospital."

Data source: medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

Of the nearly 30% of other injury cases, the bulk were reported to have taken place in emergency rooms, while surgical, internal medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology departments also reported incidents.

Yu Ming is an ER doctor assigned to Beijing Emergency Center's ambulance service. He said that attacks on medical staff in the ER is "frequent but usually not severe. "ER rooms do have more medical conflicts. Sometimes people are emboldened after drinking. Generally, they use their fists and feet (to beat doctors). They might choke a doctors' neck. Sometimes they even beat doctors with anything at hand, but things are often not particularly serious."

Slaps And Curses,

Where Do They

Come From?

Dissatisfaction with the medical services and treatment outcomes provided by doctors are the main reasons why patients physically attack doctors, according to the incidents reported by media. "Bad attitude," "failure to cure, "low professional level" are common accusations patients or their families use to justify violence.

Data source: medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

Yu Lu is a young doctor at People's Hospital of Yanliang District in the northern city of Xi'an. In October 2017, her hospital received a prematurely born baby with jaundice. "There was no problem with the treatment procedure, but the child unfortunately passed away," said Yu. Since preemies are more fragile, any number of internal or external factors can prove fatal.

However, the child's family members saw things rather differently. Although, the baby's prime indicators were normal on his last night, the family was suddenly told the next morning that the child’s situation had deteriorated and had to remain in isolation.

His death and the hospital's perceived indifferent attitude ignited negative emotions among family members. They believed the hospital was being evasive and deliberately vague about what had happened, and since the doctors could not provide a clear cause of death, they were held ultimately to blame.

It was not an easy time for Yu, though she was not directly involved in the matter. "A dozen of people laid out wreaths, played funeral music and hung strongly worded banners in front of the main gate. Doctors and other patients had to take a detour through the side gate," Yu said with a long sigh.

In addition to patient dissatisfaction, drunken behavior is another major trigger of violent incidents. People under the influence lose their restraint and become physically aggressive, turning the hospital into the scene of high drama.

Yu Ming recalled making one midnight ambulance out-call where the patient was roaring drunk. As he began gradually realizing what was happening, the patient, driven by alcohol, started abusing Yu and his colleagues. After arriving at the hospital, he kicked one doctor to the ground then began threatening Yu and the driver with items taken from the ambulance.

The patient then proceeded to smash the vehicle's windows and sideview mirrors and chased the driver into the hospital. The intake room was thrown into turmoil and it wasn’t until police arrived that the chaos subsided.

"We all got frightened, but luckily we all managed to avoid it in time," Yu said.

Blood And Bruises,

How To Protect

Medical Staff ?

Back in 2007, Liu Linfeng was on the night shift when his hospital received a college student apparently stricken by a sudden heart attack. After running a series of tests, Liu concluded the patient's condition wasn't serious and prescribed bed rest. That did nothing to reassure the family members, however, who accused Liu of neglecting his duty.

In a flash, a male in the group rushed up and slapped Liu so hard in the face, it felt like a firecracker had gone off in his ear. Intense pain and a nosebleed, followed but Liu said he was more stunned than anything. "I was full of good intentions to treat him, and the reward was an inexplicable slap."

Security staff arrived and pulled the two men apart. The now apparently recovered patient quickly slipped away with the family members before police could arrive. It was if the incident hadn’t occurred at all.

"It's impossible to rationalize it when you run into this kind of thing. Midnight troublemakers most likely will have been drinking. They run away before the police arrive after beating you, so you don't have time to call the police at all. Even if the police do come, all they can do is just ask some questions and take a simple statement," Liu said.

Data source: medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

In nearly 40% of the incidents of medical violence reported, no mention was made of any follow-up. Among those that did, administrative penalties were the most common form of punishment, including 10 to 15 days of detention or a fine of several hundred dollars. Some reports state only that a person had been "criminally detained," or "arrested according to law", or that "police have opened an investigation" without any substantive word on the results of such actions. Statistics indicate that reports involving criminal penalties accounted for less than 5% of the total.

Yu Ming believes media needs to reports on specific penalties to have a deterrent effect. "If the media does not clearly state the punishment these people received, it fails to warn the irrational, and it is not conducive to solving the problem."

Liu pointed out that police have categorized such cases as minor disturbances rather than applying more serious charges such as "picking quarrels and provoking troubles," or "disturbing public order." Light punishments can do little to deter future offenders.

"In medical conflicts, the patient is considered the weaker party, given their lack of professional knowledge, powerful background and sufficient funds. People then tend to blame doctors when they were beaten by patients. Once there is a medical dispute, the hospital will hasten to pay some money in compensation regardless of whether the medical staff was in error," Liu said.

The concerned government departments have also realized this problem. In 2015, the Criminal Law Amendment (IX) was promulgated, in which the crime of destroying medical order was included in the crime of "disturbing social order" for the first time, setting out prison sentences of three to five years for the "chief actor." In 2016, the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the Central Comprehensive Management Office, the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Justice jointly launched a one-year special campaign to crack down on medical-related violence. In 2018, the "Regulations on Prevention and Treatment of Medical Disputes" was implemented, urging the Ministry of Public Security and other relevant departments to crack down on medical crimes in accordance with the law and advocate more ways to resolve medical disputes.

Trace The Problem:

How Can We

Solve It ?

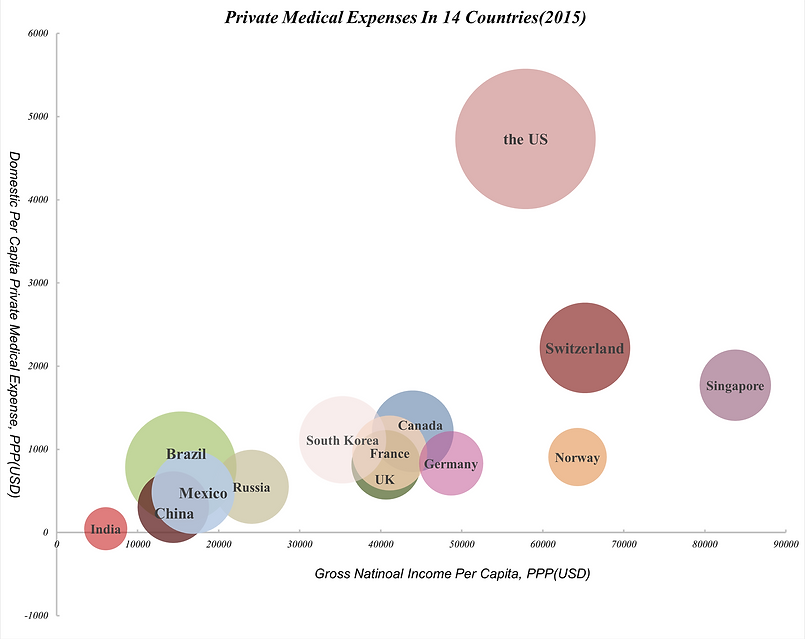

Conventional wisdom holds that high medical costs and low government subsidies are also a cause of the high frequency of medical conflicts. When people cannot afford the costs of visiting a hospital, seeing a doctor or purchasing necessary drugs, their resentment gradually builds until they choose to violent vent at medical staff.

Source: the World Bank Development Indicator 2015

Each dot represents a country: the closer to the upper right , the greater the proportion of government spending in health care;

The larger the dot, the more government medicaid the country's citizens enjoy

Based on the World Bank's latest statistical data, China's current level of government medical investment has yet to reach the global average, let alone that of developed countries in Europe and North America. Switzerland has the highest level of government medical investment, amounting to more than a quarter of government expenditure. In contrast, Chinese governmental medical expenses account for only 3.2% of GNP (Gross National Product), and 10% of the gross government expenditure.

Nevertheless, average personal medical expenses in China are not very high. According to 2015 data, private medical expenses account for about 40% of total medical expenses in China. In other words, if someone wants to see a doctor in a local hospital, 60% of all medical expenses can be reimbursed. China's annual per capita private medical expenses are about 1,066 CNY (152 USD), accounting for only 2% of the total per capita income, equivalent to 1/30 of the United States, and lower than the world average. Compared with other countries, China's personal medical costs are relatively low.

Source: the World Bank Development Indicators 2015

Each dot represents a country: the closer to the lower right, the less it spends on private health care;

The larger the dot, the greater the proportion of per capita private medical expenditure to per capita gross income

In Liu's view, the incomplete national medical policies share the blame for the intensification of medical conflicts between doctors and patients. "Up to a few years ago, the prices of most medicines were set by the government and were the same everywhere. Overpriced medicines, however, could bring doctors commissions of up to 20% per box. Some unscrupulous physicians therefore casually overprescribed to make money. The media seized on such negative cases in their reports and as a result, readers developed bad impressions of all medical workers and gradually lost faith in the profession."

Ironically, one reason behind the current violence against doctors is their new restraint in prescribing. "At present, China has rectified the chaos in the medical industry and imposed restrictions on how much medicine can be prescribed. Our hospital stipulates that the cost of medicines in each department cannot exceed 23% of the total budget. Even exceeding that by 1% will result in a fine." Said Liu. "Now doctors are afraid to prescribe medicine, but some patients don’t understand. They feel like 'If I spend my money, there is no reason doctors should refuse to prescribe the medicines I want.'"

"The medical policy is like a pendulum to some extent, swinging back and forth. But no matter which way it goes, it can always hit the doctor," said Liu, again displaying his wry smile.

Huang Zhiqiang has been a doctor in Xiamen Second Hospital for nearly 15 years. He believes medical conflicts in China are both a historical legacy and an embodiment of the current backward social attitudes toward doctors. "At present, the medical industry is widely seen as a service industry in China. People treat doctors like restaurant waiters, thinking that doctors should work for them as long as they pay money to the hospital. This is absolutely wrong," Huang said.

In Yu Ming's opinion, medical conflicts are also largely due to misconceptions about the medical profession, but of a different sort. He believes that mass media's idealization of the medical industry has created many unrealistic expectations toward doctors among the public. "The media advocates that doctors are 'angels-in-white'. On TV shows, teams of doctors carrying various equipment are shown rushing to the patient when the ambulance being called. You can see doctors awaiting the ambulance at the hospital gate in order to start treatment immediately. But these images are actually far from reality. Doctors in the real world are never so omnipotent."

"I really hope that media propaganda, film and television works can restore the doctor's real image and working status. In this way, patients can understand that doctor is also an ordinary occupation, and better communication between doctors and patients can be facilitated."

Acting on a tip received in September, 2018, reporter Wu Xinpeng of the China Youth Daily's Bingdian Weekly traveled more than 1,000 kilometers to a town in the central province Hubei to interview an anesthesiologist who had been assaulted by family members of a patient. Through his reporting, he came to a different understanding of the source of medical conflicts.

The cause of the tension between Chinese doctors and patients, in Wu's view, cannot be simply attributed to any one side. "Doctors have to receive a large number of patients every day, and it is unrealistic for them to attend to the thoughts and emotions of each one. Besides, doctors are a group with a high sense of professional accomplishment. When faced with excessive requirements from patients, they may take offense at not being understood. This accumulation of 'grievances' is likely to contribute to friction between doctors and patients," said the young journalist.

Future Prospects:

How To Improve

The Situation ?

If one looks only at the number of reported incidents of medical violence, the toughest period for doctors seems to have passed. However, more subtle tensions between physicians and their patients have yet to fundamentally dissipate.

Data source: medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

Though acknowledging that doctors were being assaulted less in recent years, Yu Ming still feels pessimistic. He finds that patients nowadays vent through verbal abuse, rather than with their fists as was often the case several years ago.

"We are often abused by the patients when going to the clinic. The only thing we can do is do our job quietly, for fear of inciting friction and causing greater conflict," said Yu Ming. "We act on the principle that we should lower our mentality and not regard ourselves as doctors, but rather as nannies to our patients."

Huang agrees there have been some changes in the nature of present medical conflicts. "Former themes of such conflicts were mainly about the patients' dissatisfaction with doctors and nurses. Now they create disturbances for other reasons," he said. "Some patients make trouble over not having delicious food in the hospital, some over the high cost of medicine. Some patients even make trouble because they fell off when getting up at night." According to him, these matters are completely irrelevant to physician responsibilities, yet many patients use the doctor as a punching bag to vent their emotions, creating an "unbearable heaviness" for those in the profession.

Data source: comments on a weibo post about Peking University Hospital's injury incident;

The larger the font size, the more frequently words appear;

"Severe punishment", "sadness", "disappointment" and "chilling" are most noticeable

Wu Xinpeng recalled the difficulties he encountered while selecting the topic of his report. "There is a bit of awkwardness regarding the timing of writing about medical doctor-patient conflicts. On the one hand, the relationship between doctors and patients has improved somewhat over the past few years. The text might be limited in range and value to society. On the other hand, negative between the two groups involved might be further aggravated if they are dissatisfied with how the story is told," Wu said. "After a discussion with the editor, I decided to present the conflicts from multi-angels by telling an integrated story."

Later, Wu tried his best to locate and communicate with each party involved in the incident. He found the doctor who had been assaulted, his family members and colleagues and the police who dealt with the conflict. He then trudged out to the countryside to find the dead patient's relatives, who at the time were holding the funeral. He recorded all these different voices in his story. Referring the editor's suggestion, Wu titled the story "An Atypical Medical Injury Incident".

After it was published, Chinese medical information sharing platform DXY applied to repost it to their official WeChat account. Number of views soon passed 100,000, putting it among the platform's most viewed articles.

To Wu's surprise, the patient's relatives expressed their gratitude immediately after reading the story. "They might think that this report helped them wash away their grievances in some way."

"Doctors and patients should not be mutually antagonistic. Also, only talking about right or wrong in an all-or-nothing way does not help solve medical disputes. As a reporter, it is not my responsibility to judge right and wrong. Instead, reporters should unearth the facts, explain the causes and effects clearly, and enhance mutual understanding between doctors and patients," said Wu, choosing each word carefully.

BACK TO TOP

Planning & Production: Wan Sicheng, Li Jiangmei, Zhao Jiaqi

Adviser: Fang Jie

Contact: 2016200669@ruc.edu.cn

Data Source:

White Paper on the Practice of Chinese Physicians, 2018;

China Sanitation and Family Planning Statistical Yearbook, 2017;

The World Bank Development Indicators 2015;

Medical injuries reported by media from 2009 to 2018, collected online

© 2018 by School of Journalism of Renmin University of China. Proudly created with Wix.com